Fanon and Gramsci: The Wars of Maneuver and Position in The Wretched of the Earth

First submitted as an honours thesis for the Contemporary Studies Program at the University of King's College, Halifax (ed.).

by Isabelle Ortner

Abstract

With primary reference to Frantz Fanon’s work entitled “On Violence” from The Wretched of the Earth, I will examine the colonial maintenance of social control through violence and cultural hegemony. These tools of control keep subjugated populations from rebelling against the powers that be. I will explore the connections between Fanon’s exploration of colonial political dynamics and Gramscian terminology from the Prison Notebooks in the hopes of offering a call and response dialogue. This dialogue will demonstrate the shared calls to revolutionary action among the masses to dethrone the social, political, and economic capital hoarded by colonists and the bourgeois class. This thesis will analyze Fanon’s Algeria and Gramsci’s Sardinia to provide historical context to why these two radical political thinkers were driven to write about the social inequalities that oppress citizens under the grips of violent political regimes. I argue Gramsci and Fanon, despite their cultural differences, shared intellectual kinship in many respects. Both intellectual revolutionaries discuss the ways in which the masses are able to mobilize acts of rebellion towards a revolution by appropriating the oppressive ruling class’ tools of coercion and consent for themselves. The masses overturn state and colonial tools of coercion and consent into tactics of war of maneuver and war of position. State forces such as education; political, economic, and intellectual elites; physical intimidation and violence are repurposed and reimagined by the oppressed class to regain power over the state controls that suppress the will of the people. To shift the social consciousness against the perpetuation of the status quo, a social upheaval among the oppressive classes unveil the hypocrisy of the ruling class to subsequently be resisted. The very oppressive mechanisms that suppress the oppressed class—state violence, assumed truths of political legitimacy, and ideological dogmatism—must be deconstructed and appropriated as tools for the oppressed class to revolt efficiently and successfully. Gramsci and Fanon echo these ideas in hopes of awakening public consciousness.

Key words: war of position, war of maneuver, colonialism, revolution, coercion, consent, cultural hegemony.

Formative Times: Political Landscapes of Algeria and Sardinia

Frantz Fanon decided to leave Paris, France in 1953 where he had been a student of psychiatric medicine. France had not been the idyllic place of liberté, égalité, fraternité that he had desired the nation to be. France could not live up to the nation’s motto for a man such as Fanon. Fanon knew that there was no escaping his body schema as a Black man in a European country. He became disenchanted by the growing sense of colonial alienation he harboured. Fanon’s complexion was perceived by European colonial standards as “not ‘really French’ in France” (Omar 266). Fanon’s Martinique origins contributed to this sense of alienation. This alienation was not a unique experience, as others with backgrounds from West Indian and African countries found France to be an unwelcoming environment due to the prevalence of anti-Black racism in the white majority nation. Fanon’s move to Algeria started the formative years of his transition into the revolutionary figure thinker that he remains to this day.

The Algerian War spanned from November 1954 to March 1962. Fanon had moved to Algeria to work at Blida-Joinville Psychiatric Hospital in 1953 and worked there until 1956. He served as a psychiatrist during the bloody battles between the Front de Libération Nationale and France. Due to the prevalence of colonial rule in Algeria at this time, “a minority of Europeans ruled over a largely illiterate and cruelly exploited majority of Arabs and Berbers” (Omar 266). Fanon had left France and relocated to a country that was racially more diverse; however, he could not escape the colonial control of France. As Fanon began his medical career in Algeria, his disillusionment grew.

France believed Algeria to be rightfully theirs. Europeans were the ruling class in Algeria. This was politically apparent with the Algerian president Charles De Gaulle who was representative of French control over Algeria between 1959 and 1969.

Algeria’s brewing civil unrest proved decisive for Fanon’s work. In 1956, Fanon began collaboration with the Algerian liberation movement. He sided with the Algerian resistance; having grown up in Martinique, Fanon felt this was the ethical choice to make. Fanon lived through “the administrative abuse of his native island of Martinique” which “was not unique to the West Indian French colonies, it is understandable that, when in Algeria, Fanon sided with the natives in the resistance” (Bentahar 129). Fanon saw the injustices of violent colonial repression, while also being aware of the violence of administrative tactics that infiltrated education systems. The education system served as a tool to enrich French patriotism among students, as well as violently enforcing the historical accounts of the French who occupied Martinique since 1635.

Between his times in Martinique, France, and Algeria, Fanon had experienced first-hand how the assimilationist education, ravages of colonial violence, and civil war had left traumatizing effects on colonized subjects. Fanon had been subjected to the colonial education system in Martinique and the pattern of colonial assimilation tactics by the French had remained omnipresent in Fanon’s life. For Fanon, “His early schooling was marked by the French colonial approach to education, infamous for its assimilationist strategies” (Bentahar 129). The paternalistic approach of colonial rule was an effort by the French to enact settler assimilation tactics, hoping to ‘civilize’ the non-Europeans deemed in need of assistance in becoming Europeanized. Colonial rule of the French sought to eliminate self-government and cultural difference from colonial subjects. It is this oppressive aspect of denying self-determination and self-expression of cultural particularity which is a shared plight of Martiniquan and North African peoples. The bubbling resentment of the colonized peoples of Algeria was informed by the French assimilationist policies that were utilized in the West Indies and were also implemented on the African continent. French etiquette, language, and history were forcibly taught in the education system. The French colonial rule additionally had overt tactics to preserve assimilation tactics in Algeria. The use of physical violence through police and military coercion was used to subdue and control the groups and individuals resistant to the colonial enforcement of the nation.

The use of violence against Algeria’s people was ruthless and lethal. Sartre writes in the preface of The Wretched of the Earth, “Our beloved values are losing their feathers; if you take a closer look there is not one that isn’t tainted with the blood” (Fanon, lix). Here, Sartre boldly critiques the hypocrisy of French values such as generosity and fraternity which have been abandoned for brutality. Sartre continues, “What about those eight years of fierce fighting that have cost the lives of over a million Algerians?” (Fanon, lix). Sartre points out the scale of the documented lives lost in order to illustrate the extent of anguish the colonial order had caused. The power struggle that occurs in the process of decolonization is in full force and the Western efforts to subdue it will inevitably result in more casualties for the fight for freedom.

At 18, Fanon had served in World War II with the French Free Forces, despite racism towards non-white citizens, which treated them as backwards and uncivilized. During his time in the French Free Forces swiftly after leaving Martinique in 1943, he had been discriminated against due to his race and his racial consciousness became wary of the European attitudes toward racial difference (Bentahar 130). Violence was considered a patriotic, valorous endeavour when citizens fought for their country during the war. This understanding of patriotic violence stands in stark contrast to the violence that arises during insurgencies against the ruling class within the nation. The violence inflicted against Algerian resistance groups fighting for liberation from the French colonial order during the Algerian War were treated by the French as unpatriotic and needed to be vanquished with excessive physical force. Sartre states, “killing a European is killing two birds with one stone, eliminating in one go oppressor and oppressed: leaving one man dead and the other free; for the first time the survivor feels a national soil under his feet” (Fanon lv). When Fanon fought for the French, he had left his home soil of Martinique and had contributed to the war efforts in a country which fought for the national strength of France. The colonial rulers only acknowledge the legitimacy of their colonial state and encourage patriotism through fighting for the colonial state against foreign enemies. When an individual or group turns on the colonial state and denounces patriotism in favour of violence against the colonists, national soil becomes a free for all. When the colonized fight for ownership over their rightful home soil, this brings attention to the fact that the land is stolen. The colonists desire to be the victors of the terrain and therefore the only condoned violence is the patriotic violence of the state’s military.

The violence during the Algerian War fundamentally can be understood as the fight for autonomy over the rightful national soil of the colonized. Fanon was deeply involved in the political turmoil of the period and began to notice the detrimental impact that the Algerian War had physically and psychologically harmed citizens. He came to the conclusion during his medical evaluations that “the colonial situation has become a favourable breeding ground for mental disorders” when working at the hospital with Algerian victims of violent torture (Omar 266). His resignation from his colonial post at the hospital in 1957 marked the formative time to not only write revolutionary works about the psychological and political impacts of colonialism, but also to physically work in solidarity with the colonized peoples. Fanon allied himself with the Algerian National Liberation Front (FLN) which sought to gain control over the land by forcible arms if necessary in order to eject the French colonial rule which occupied the North African region. Fanon empathized with the colonized non-European Algerians because he knew what it was like to be racially devalued. Through violent confrontation with the French, the Algerian resistance gained independence in 1962. Despite this victory, Fanon wrote about the underlying dynamics between the colonialist and the colonized groups in an effort to get to the root of colonial oppression and revolutionary retaliation.

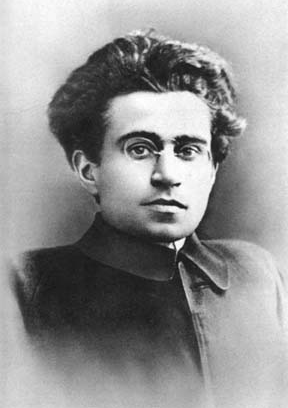

The Introduction to the Prison Notebooks describes Gramsci’s early years which were impacted by violent repression in Sardinia. Sardinian peasants were “brutally repressed by troops from the mainland” (Hoare and Smith xix). Gramsci “never lost the concern, imparted to him in these early years, with peasant problems and the complex dialectic of class and regional factors” (Hoare and Smith xix). This much is clear, as Gramsci is fasly considered one of the most prominent Marxist scholars of the twentieth century.

The Prison Notebooks introduction describes how Gramsci’s adolescent years were formative for the development of his political convictions. His early years were the beginnings of his class consciousness and class solidarity with his fellow peasant class Sardinians. The introduction states, “A unique surviving essay from his schooldays at Cagliari shows him, too, already progressing from a Sardinian to an internationalist and anti-colonialist viewpoint” (Hoare and Smith xix). This detail is essential to note as it demonstrates Gramsci’s thought, as I will recount later, can be applied internationally. Fanon's critique of colonialism or anti-colonial thought harmonizes with Gramsci's internationalist thought. Gramsci’s internationalist and anti-colonial thought is stoked as an adolescent as he had opposed European imperialism and had not supported the imperialist efforts in foreign countries such as China (Hoare and Smith xix).

The 1906 social uprising in Sardinia was an effort to assert the island of Sardinia’s economic autonomy in relation to the Italian mainland. Troops were sent from mainland Italy to Sardinia in order to enact coercive repression onto the peasants of Sardinia to thwart their revolutionary goals of independence (Hoare and Smith xx). The brutality in Sardinia was one formative factor that showed Gramsci what repressive governmental and military oversight looked like. Another factor leading to Gramsci’s radicalization was the return of his older brother Gennaro, who had returned from his military service in Turin and had become a socialist militant (Hoare and Smith xix). Gennaro’s time in mainland Italy had radicalized him and from 1906 until he had returned home to his brother Antonio, Gennaro had sent his brother socialist pamphlets (Hoare and Smith xix). This served as a radical introduction to political life. Gramsci discerned the inequalities between the industrial, urbanized regions and the peasantry in rural regions of Italy.

Gramsci would continue to advocate for the Southern Italian peoples, including those in Sardinia, who were divided from the industrial Southern Italian regions. Gramsci encouraged the collaboration of the Southern peasant masses to articulate their desire for equality with the North of Italy. The North consisted of many bourgeois citizens and the South of less affluent proletariats. Gramsci himself was born into peasantry in Sardinia, and so it subsequently was an act of class solidarity. This act of solidarity echoes Fanon’s decision to ally himself with the Algerian resistance that opposed the European colonial stronghold in North Africa. Akin to Fanon, Gramsci could see himself in the resistance of the marginalized and this ethically and philosophically bound him to analyze the reasons certain groups resist power, while others seek to maintain their power within the state apparatus.

In 1926, Gramsci was the leader of the Italian Communist Party. That year, he was imprisoned by Mussolini’s fascist government. He was imprisoned due to Mussolini’s wish to remove the oppositional political perspectives, which Mussolini considered a looming threat to his political control. From 1926 to 1934, Gramsci was imprisoned. It was in prison that he wrote Prison Notebooks. Despite his sentence to prison being twenty years, he was sent free in 1934 due to poor health. He died for his convictions under the fascist regime, until the end of his life writing about the rights of workers and the maladies of capitalism.

Antonio Gramsci passed away when Frantz Fanon was twelve years old. This generational disconnect only further intrigues how the two seem to speak to one another in their theoretical approaches. It is additionally fascinating that the geopolitical landscapes of their respective experiences in Algeria and Sardinia varied in their cultural and historical contexts, yet the theoretical realizations that arose from these contexts have a shared consciousness of the disparities between the urban, colonist, and non-colonist elites with the rural masses.

Gramsci, though never in contact with Fanon as they lived in different time periods and regions, similarly took revolutionary stances in his political writings as well as his personal political ideologies. The merging of personal beliefs and the texts produced by Gramsci and Fanon can be seen, I argue, to be the result of academic writings agitating the cultural hegemony controlled by government, as well as establishment academics and groups with vested economic interests in upholding the political status quo. Gramsci and Fanon’s personal experiences of civil unrest and repressive government regimes informed their radical theory due to their own political convictions in their lives. The Wretched of the Earth and Prison Notebooks embody these convictions.

There is no one single vantage point of revolutionary action. Political resistance and revolution exist in both spheres of physical violence that uses force to preserve a coercive domain of control over the masses, as well as through cultural hegemony that wishes to keep all citizens to accept rather than critique the intellectual discourse, social norms and values, morals, and political dogma that the most powerful groups within society wish to maintain hegemonic rule. Before I explore the world of cultural hegemony which pervades intellectual institutions and urban elite capitalists, I will explore the ways in which oppressive regimes weaponize violence versus how revolutionary violence re-imagines the oppressive tool of violent coercion in order to assert autonomy within a resistance movement.

Gramsci’s War of Maneuver in “On Violence”

Gramsci’s war of maneuver is the physical struggle of frontal attack and defence which stands as a swift and particular event among marginalized resistance groups. War of maneuver is an abrupt assault that erupts the established order of the state and civil society. This tactic flips the accepted normalcy of coercion within the state and appropriates the use of violent insurrection into the hands of those not in positions of governmental and military power. The war of maneuver, although it is not used in Fanon’s terminology in The Wretched of the Earth, nevertheless is transposed into the context of Fanon’s work. Gramsci’s war of maneuver can be internationally applied to the colonial context of Algeria’s war of independence and Fanon’s justification for physical force.

Gramsci uses Machiavelli’s Centaur which is the dual embodiment of half animal and half human. This portrayal delineates the difference between coercion (the war of maneuver) and consent (the war of position). Gramsci distinguishes between the dual nature of the Machiavellian Centaur. He states, “They are the levels of force and of consent, authority and hegemony, violence and civilization, of the individual moment and of the universal moment, of agitation and of propaganda, of tactics and of strategy” (170). The Centaur is seen to represent the two sides of the state. There is the half animal side of the state which can be characterized by violence, force, and agitation. Acts of coercion are present within the state in various manifestations. Predominantly, coercive force is seen in the political sphere to gain control of the citizens dwelling within the state. The other half of the Centaur which consists of the human side is defined by consent. The human half is the cultural side in which hegemony, propaganda, and civilization are prominent. The citizens consent to power wielded over them by the dominant bourgeois class. The bourgeois class makes the particular interests of their class the universalized interests of the general public. These interests serve the dominant class, however, through cultural permeation, the masses are led to believe that the interests of the powerful are beneficial to the masses’ best interest as well. While the beast side of the Centaur signifies the coercive nature of the political sphere, the human side reflects the interests of the dominant class which are perpetuated through culture, civil society, and institutions.

Fanon begins The Wretched of the Earth with a militant declaration. In his first chapter entitled “On Violence,” Fanon writes, “National liberation, national reawakening, restoration of the nation to the people or Commonwealth, whatever the name used, whatever the latest expression, decolonization is always a violent event” (1). Fanon leaves no room for flowery interpretation. Colonized peoples and colonists form a dichotomous relationship or dialectic in which one group is defined by the other in a region of colonial oversight and control. The wretched peoples or the damnés are the colonized peoples who are subjected to the cruelties of the colonists in the repressive state. The antagonism of the damnés and colonist dialectic is a violent encounter under colonial rule. Violence is a weapon of dehumanization toward the colonized. The colonist’s image of the colonized is distinctly inhuman. This image of inhumanity propels the justification for the cruelties inflicted against the colonized peoples. Colonial society is scarred by perpetual brutal social control that aims to remind the colonized of their perceived inhumanity with conspicuous state violence enforced by police officers and military soldiers. The profanely conspicuous, as I will refer to non-covert, repetitive state sanctioned violence toward the public, is what grows the resentments of the colonized peoples. The state violence replicates itself in its practice. The seething resentment of the colonized must be kept from bubbling over into public conflict.

Fanon writes, “In its bare reality, decolonization reeks of red-hot cannonballs and bloody knives” (3). The damnés take the colonial project’s violence and turn it on its head and send it hurtling toward the colonist, “breaking his spiral of violence” (Fanon 9). The profanely conspicuous is therefore reappropriated for efforts of colonial liberation and does not attempt to be covert in its operation. The statement of the violence asserts the autonomy and humanity of the colonized subjects that participate in the violent conflict. The war of maneuver that the damnés enact is in stark contrast to the war position which will be examined later on, which acts in a subtle manner to alter the cultural hegemony as it stands.

The fight for independence from the grips of colonialism is not propelled by a rosy promise of immediate social, economic, and political harmony once a new, independent state arises. New, developing countries do not evolve overnight. Rather, the motive is an assertion of the image of the colonized as human beings with dignity who have the capability to exercise their free will without being crushed by the colonial project. Through violence, “new men,” will emerge from the decolonization of the state. The colonial subjects will be redefined not through the colonialist, but as their own image of themselves. The previous perception of colonized peoples projects dehumanizing qualities onto the subjects. The colonial subjects, through war of maneuver, break free from colonial oppression through the appropriation of violence.

The violence that was once targeted toward the damnés is repurposed for the use of the colonial subjects who cannot withstand the violent oppression any longer. It is in repressed rage and terror that the colonized peoples finally flip the oppressor and oppressed dynamic through the use of force that the colonists rely upon to maintain power. Sartre explains this shift of violence in the preface. He asserts, “At first the only violence they understand is the colonist’s, and then their own, reflecting back at us like our reflection bouncing back at us from a mirror” (Sartre li). Sartre poignantly explicates the effects of violence as a tool for liberatory rebellion. In essence, Sartre comments on the appropriative nature of violence in a colonial schism. The colonist instigates the hostile relationship between colonist and colonized peoples through coercive violence to maintain colonial domination. Colonized populations grow resentful and retaliate using the tools available and most familiar to them: the war of maneuver originally inflicted upon them. The colonial oppressors are enraged by this and continue their violent repressive tactics. Fanon states, “Violence among the colonized will spread in proportion to the violence exerted by the colonial regime” (46-47). Sartre described decolonial violence as a mirror. Fanon complements Sartre’s assessment. The act of decolonial violence appropriates state violence in order to give back control to the colonized masses. Violence is met with violence of equal measure to gain this control.

Fanon describes the war of maneuver enacted by colonized peoples as the mechanism through which the humanization process can begin—where the damnés and colonists are treated as equal autonomous groups. Not only does violence articulate the humanity and agency of marginalized peoples previously under violent state repression, it also becomes a power struggle where two equally dominant groups fight for sovereignty and freedom from rule by the other party. Fanon states, “the violence which governed the ordering of the colonial world, which tirelessly punctuated the destruction of the indigenous social fabric...this same violence will be vindicated and appropriated when, taking history into their own hands, the colonized swarm into the forbidden cities” (Fanon 6). Significantly, Fanon expressly uses the term appropriation to demonstrate that the appropriation of the oppressor’s violence is an act of retribution. He asserts that the violence which has tarnished the cultural fabric of the Global South is justification in itself for colonized peoples to assert their agency. Acting as agents for the decolonization project, the colonized avenge their culture and historical narrative through violent retaliation toward the colonizers. The acts of violence help the indigenous peoples reclaim ownership of their historical narrative, cultural identity, and agency.

Fanon alludes to reclaiming autonomy through replacing the colonizer. He writes, “The famous dictum which states that all men are equal will find its illustration in the colonies only when the colonized subject states he is equal to the colonist. Taking it a step further, he is determined to fight to be more than the colonist. In fact, he has already decided to take his place” (Fanon 9). The damnés desire to ensure they will be treated as equals to the colonists. To ensure there will be no further oppression, the damnés use violence through diminishing the colonial occupier’s military and taking their place to continue the process of decolonization. Gramsci writes in his chapter on “Political Struggle and Military War” the following: “In military war, when the strategic aim—destruction of the enemy's army and occupation of his territory-is achieved, peace comes” (Gramsci 229). The violence is a strategic way to ensure the absence of future oppression and to keep peace in the territory. Replacing the occupier negates the presence of a political antagonist.

Fanon states how violence is an equalizer which forces the colonist to see the colonized as a fully human and equally capable agent. Taking this further, Fanon scholar Lewis Gordon explains that there is a misconception that Fanon does not want to be treated as the so-called ‘other’ by Europeans. This misconception implies that Fanon would have desired to be treated as if he were a European himself. Gordon argues in his lecture video entitled “What Fanon Said,” that racism is not about the common conceptualization of racism that it centres the self-other dynamic. The discourse surrounding racism underlines the desire to not be ‘othered’ by white people. Gordon urges us not to fall into the trap of this cliché. He adds that Fanon had identified the nuance between the ‘other’ and the ‘subhuman’ (Gordon 29:00-30:00). Being othered implies being a human who diverges from white normative identity and is therefore treated as someone alien from oneself. To be othered does not mean that one is treated in a brutalizing, inhumane manner. Rather, it is a mode of differentiation and alienation between those in varying racial and ethnic groups. Gordon states that there exists the self, the other, and those outside of the realm of the self-other dynamic. Those outside the self-other dynamic dwell in what is referred to as the zone of nonbeing (Gordon 29:00-30:00). The zone of nonbeing is where those considered subhuman dwell and where brutality inflicted by the oppressor is able to thrive.

Gramsci warned not to overestimate the effectiveness of only utilizing this warfare tool in his chapter entitled “Political Struggle and Military War.” He writes, “to fix one’s mind on the military model is the mark of a fool: politics, here too, must have priority over its military aspect, and only politics creates the possibility for manoeuvre and movement” (Gramsci 232). Here, it is noted how Gramsci does not overemphasize the importance of war of maneuver on its own as a tool for revolutionary action against the imperialistic, capitalist state apparatus. Here, we are reminded of the Machiavellian Centaur. There must be balance in the use of violence and the use of influencing the cultural hegemony. Gramsci points to the war of position as the viable tool of infiltrating systems of power which uphold cultural hegemony.

Gramsci’s War of Position in “On Violence”

Before defining the characteristics of the war of position, it is crucial to underscore the defining features of cultural hegemony. Cultural hegemony is defined in the chapter entitled “The Formation of the Intellectuals” as “The ‘spontaneous’ consent given by the great masses of the population to the general direction imposed on social life by the dominant fundamental group” (Gramsci 12). The bourgeois ruling class hold the cultural power within a given society. The proletarian masses give their consent to this hegemonic power through the imposed social norms dictated by the dominant bourgeois class. The hegemonic power of the ruling class is achieved through the consent of the masses who may not know what they are agreeing to. The masses accept the rules of engagement in society while the bourgeois class use cultural hegemony to attain and maintain power. The ruling class maintains dominance over ideological and cultural modes of society. Cultural ideas control the citizens when the masses accept the ideas that are provided to them as normative. Therefore, the status quo implemented by the bourgeois is difficult to alter because citizens do not think to question the normative ideas that are pervasive within civil society.

Notably, the hubris that this influence on society gives the ruling class only solidifies the societal mythology that the ruling class is worthy of the position it maintains. Gramsci argues, “this consent is ‘historically’ caused by the prestige (and consequent confidence) which the dominant group enjoys because of its position and function in the world of production” (Gramsci 12). The cultural hegemony functions as a prison that restricts freedom from the proletariat masses. How can the masses free themselves from the cultural influence of a class that does not have their best interests at heart? To live in a culture of capitalism is harmful to the proletarians who do not benefit from such an economic apparatus. The culture of capitalism remains an integral part of the cultural hegemonic superstructure. The superstructure is made up of the civil society and political apparatus of a given society. When civil society’s accepted cultural norms are dictated by the ideologies of the bourgeois class, the citizens are not immersed in a societal environment that is conducive to resistance to the status quo. The Marxist prophecy of the rise of the proletariat becomes hollow and unfulfilled. This prophecy cannot be fulfilled without a revocation of consent from the masses. While the Gramscian war of maneuver relies on physical, spontaneous acts of resistance, cultural hegemony requires resistance in the form of the war of position.

The hegemon must be undermined through the war of position. The war of maneuver alone cannot successfully maintain long lasting change. The war of maneuver gives agency to the oppressed class that uses violence. However, the war of maneuver is a spontaneous struggle that creates turbulent social and political environments. Long-term political and social shifts require infiltrating the hegemon. The war of position relies on reformation within the hegemonic superstructures that dominate a society. Infiltrating the hegemon therefore can restore ideologies and cultural norms in civil society to properly represent the interests of the oppressed masses, whether they be oppressed under bourgeois rule or colonial rule.

The war of position is considered the passive form of revolution. What makes this form of revolution passive is the emphasis on shifting what values, norms, and interests are considered the status quo. In doing so, citizens consent to the new order in a passively engaged manner. There is no coercive tactic involved whatsoever. The war of position is fundamentally a cultural struggle. Fanon and Gramsci both turn to the intellectual as an influential avenue for infiltration of the hegemon.

Within the hegemonic apparatus, there is a group of intellectuals that protect the cultural hegemonic order and prevent infiltration of the hegemon. Gramsci refers to this group as the traditional intellectuals. The traditional intellectuals are part of the cultural elite. Through rigorous education, certain citizens acquire roles in society that are held in high esteem such as teachers, artists, writers, philosophers, and so on (King 25). The traditional intellectuals earn high esteem and gain their knowledge from intellectual culture. The hegemonic superstructure is upheld by the reproduction of intellectual culture. Traditional intellectuals produce work that contributes to the culture and therefore supports the culture’s legitimacy within society. The traditional intellectuals “perceive themselves and are perceived as an independent social group. But they are not; they too are possessed by history” (King 25). Despite the belief that they are outside of the grips of hegemonic influence, the traditional intellectuals are an integral component of cultural hegemony. There is no freedom of expression for the traditional intellectual because they rely on the cultural legacies of the past in order to express themselves.

The intellectual tradition is realized through the creation of intellectual disciples who follow the path of intellectuals of the previous generations. Sets of norms and values, narratives, and propaganda within intellectual culture are established by the dominant bourgeois class. The interests of this class carry through the intellectual tradition and therefore does not have a vested interest in changing the status quo. The traditional intellectual secures the dominance and authority of the elite class and in doing so, ensures the consent of all social groups within society.

Fanon touches on the idea of the elite, traditional intellectual in “On Violence.” Fanon asserts that intellectuals who reside in colonized countries fall under a political category labelled the national bourgeoisie. The national bourgeoisie are individuals who align themselves with the Western bourgeois class. Their values and motives cater to the colonists who desire to maintain control of their countries. The national bourgeoisie conform to Westernized life and do not align themselves with the peasant masses. The national bourgeoisie, often diplomats and intellectuals are thrown to the forefront of negotiation with the rebellious masses. They are chosen to do so specifically because they have not broken ties with colonialism (Fanon 24). Typically, those who are part of the national bourgeoisie are considered cultural mediators between the colonized masses and the colonists. The national bourgeoisie are the elite of the colonized countries and as part of their role, defer to the colonists in administrative and political matters. The two foundational similarities between Gramsci’s traditional intellectuals and Fanon’s national bourgeoisie is the elite status the positions hold in society as well as the lack of revolutionary instinct. The national bourgeoisie and traditional intellectuals benefit from the bourgeois cultural hegemonic interests remaining dominant within civil society. These two roles additionally have no revolutionary motivations for liberating the oppressed factions of the general public. Therefore, both are obstacles in the path to national liberation from colonial rule.

The national bourgeoisie are forced to be mediators between the masses and the established political order to avoid an insurrection against the colonial regime. They are thrust into the role of the beacons of compromise in the hopes of settling the agitated masses. The national bourgeoisie are fearful that “they will be swept away, and hasten to reassure the colonists: ‘We are still capable of stopping the slaughter, the masses still trust us, act quickly if you do not want to jeopardize everything’” (Fanon 24). The masses have the capability to destroy everything that the colonial regime has established. The national bourgeoisie are delegated to de-escalate any potential violence to the colonial state by the colonial overseers. This causes the national bourgeoisie to be viewed as traitorous to the liberation movement.

In order to be liberated from the colonial rulers, there has to be leaders who do not moderate and compromise between parties. The colonists ask for diplomacy and pacifism in order to delay an insurrection on behalf of the colonized peoples. In the hopes of avoiding the process of decolonization, colonial administrators contact elites of the colonized world in order to compromise their way into halting the shift toward equality among all inhabitants of a colonized state. Gramsci provides an example of a group that is able to infiltrate the cultural hegemony. The organic intellectuals are able to infiltrate the intellectual culture in a manner that can undermine and dismantle the dominant cultural influence that the colonial, bourgeois group safeguards. The introduction to “The Intellectuals” chapter of Prison Notebooks elaborates on the role of the organic intellectuals. They “are distinguished less by their profession, which may be any job characteristic of their class, than by their function in directing the ideas and aspirations of the class to which they organically belong” (Hoare and Smith 3). The organic intellectuals are not of value to civil society based on their status within the social hierarchy. Rather, they are valuable because of their use as the catalysts for change. A counterculture is put into action by the organic intellectual. The counterculture appropriates the hegemon’s ownership of dominant cultural ideas and uses the hegemon’s authoritative voice to change the cultural norms and ideas. In essence, the organic intellectuals use the intellectual hubris of the traditional intellectual to demand authoritative legitimacy.

The counterculture opposes the status quo of the cultural hegemony devised by the bourgeois class. In essence, “The organic intellectuals serve as a link between their own class and the traditional intellectuals” (Hoare and Smith 4). While Fanon’s national bourgeoisie is a link between the colonist and the damnés which thwarts revolutionary action, the Gramscian organic intellectual catalyzes the process of revolution. The organic intellectual mediates between the traditional intellectual and the interests of their own class, which is often of a lower status than the bourgeois class.

The organic intellectuals are able to change norms and ideologies from the inside of systems of power. The “Organic intellectuals are the members of each social group who, whatever their profession or economic role, create the ideas which rationalize and justify the interests of their own social group and its claim to dominance” (King 25). This group is essential to liberation movements. The organic intellectual expresses the sentiments of the masses who cannot express their ideas themselves due to the barriers of intelligentsia elitism. Organic intellectuals themselves are often underrepresented in intellectual circles. The traditional intellectuals and national bourgeoisie are out of touch with the interests of the masses. It is the organic intellectual that has the ability to express the thoughts of the subaltern. The subaltern are the marginalized, displaced social groups in society. The organic intellectuals have the potential to lead civil society and political life to a revolutionary vision because they are not interested in maintaining traditional intellectual culture.

Both Gramsci and Fanon cast traditional intellectuals and national bourgeoisie in a light that is incompatible with revolutionary thought or action. It is Fanon’s colonized intellectual that must become an organic intellectual in order to strengthen the liberation movement of the masses. When armed liberation struggles gain momentum, this causes the colonized intellectual to withdraw from their prestigious role and re-evaluate their values. Over a long period of armed struggle against the colonial state there is an “effective eradication of the superstructure borrowed by these intellectuals from the colonialist bourgeois circles. In its narcissistic monologue the colonialist bourgeoisie, by way of its academics, had implanted in the minds of the colonized that the essential values—meaning Western values—remain eternal despite all errors attributed to man” (11). Revolution shakes the foundations of the dominant cultural hegemony and questions its legitimacy. The traditional, colonized intellectual, for Fanon, begins to realize that the interests of their social group are finally being fought for. The interests that the intellectual is defending do not suit the needs of the intellectual as a member of their subaltern social group.

The traditional intellectuals realize they are protecting the Western ideologies that do not benefit them. The traditional, colonized intellectuals will break free from the Western cultural value of individualism and eurocentrism and begin to see the value in their community assembly (11). I argue, it is then that the traditional, colonized intellectual can transform into the organic intellectual to assist the revolutionary masses. Their intellectual strengths can be used to create counterculture education that aligns with the liberation struggle. The implementation of an alternative education which critiques the values of the cultural hegemony would embolden citizens to take political action or to build a new intellectual culture. Violence is not only physical. It is the struggle for counter-hegemonic cultural recognition.

Conclusion

I argue that Gramsci and Fanon are in an eternal dialogue with one another. They may not have exchanged theoretical ideas explicitly with one another, but their similarities transcend geography and time. Both thinkers argue that resistance against the dominant, oppressive class requires the appropriation of the war of maneuver and war of position together in order to achieve liberation. The oppressed masses must turn to coercive violence and cultural hegemonic influence which the ruling class originally possessed and hold radical ownership over these tools of state power.

It is crucial to articulate that the nature of the two thinkers is an intellectual kinship. Fanon cannot be conceptualized as a thinker who is a disciple of a European thinker. Fanon is an autonomous thinker who is not derivative of a white intellectual. By stating the intellectual kinship between Gramsci and Fanon, the two are put on equal levels of intellectual merit. To call Fanon Gramscian would take away from the unique and independent theoretical approach of his work.

The two speak to one another and share theoretical themes, nevertheless, Fanon cannot be characterized as a Gramscian because to do so would be an effort to legitimize his work only through association with European thought (Gordon 20:35-21:00). To call Fanon Gramscian leaves out the reciprocity of the call and response dialogue that the thinkers have without Fanon ever citing Gramsci as an influence. I cannot claim that Fanon is a Gramscian; however, I claim they are revolutionary counterparts.

Works Cited

Bentahar, Ziad. “Frantz Fanon: Travelling Psychoanalysis and Colonial Algeria.” Mosaic: An Interdisciplinary Critical Journal, vol. 42, no. 3, 2009, p. 127–140. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/44030671.

Fanon, Frantz. The Wretched of the Earth. Translated by Richard Philcox. Grove Press, 2004, p. 1-46.

Gordon, Lewis. “Lewis Gordon Presents ‘What Fanon Said.’” Youtube. Uploaded by Red Emma’s Bookstore Coffeehouse. 13 June 2015, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UABksVE5BTQ.

Gramsci, Antonio. Selections from the Prison Notebooks of Antonio Gramsci. Edited and translated by Quintin Hoare and Geoffrey Nowell Smith. International Publishers, 1971, p. xix-232.

King, Margaret Leah. “The Social Role of Intellectuals: Antonio Gramsci and the Italian Renaissance.” Soundings: An Interdisciplinary Journal, vol. 61, no. 1, 1978, pp. 23–46. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/41178047.

Omar, Sidi. “Fanon in Algeria: a case of horizontal (post)-colonial

encounter?” Journal of Transatlantic Studies, p. 264-278.

Sartre, Jean Paul. Preface. The Wretched of the Earth, by Frantz Fanon, Grove Press, 2004, p. li- lix.